In 1979, Judy had her last Hot 100 charter with "Hard Times For Lovers" (number 66) and prior to that, she'd sung a few hits written by others. The folk artist got her first and only top ten hit in 1968 singing Joni Mitchell's amazing "Both Sides Now." A few quibbled in real time about the way such a beautiful song had been turned into cotton candy -- especially after 1969's The Mama Cass Television Show exposed the country to Joni's far more poignant version. Watching Joni strum her guitar and sing the song from the heart on Cass Elliot's ABC special and contrasting that with Judy's chirpy, carnival version, was like hearing Janis Joplin tear through "Down On Me" while Petula Clarke offered up "Downtown."

Judy would hit the top twenty later with "Amazing Grace" -- which she thankfully didn't arrange as a hoe-down number -- and again with "Send In The Clowns." She recorded on Elektra for most of her career and she really wasn't an album artist. She was forever trying to hit the charts and forever failing. A folkie with a guitar, she recorded five albums that found her billed as a Joan Baez wanna-be. The best of the five, 1965's Fifth Album, is a minor classic. It was her follow up, In My Life, that remains the finest albums she's recorded and a sixties classic. For the rest of the sixties and throughout the seventies and eighties, there were no classics -- minor or otherwise -- and Collins appeared to flounder from track to track which made 1991's Fires of Eden a genuine revelation. She followed up that classic with a tribute album to Dylan entitled Judy Collins Sings Dylan . . . Just Like A Woman which continued her winning streak; however, subsequent albums quickly indicated her streak was over. Then, in 2005, she pulled it together again for Portrait of an American Girl which was one of the decade's classics.

If there's a term for her recording career, it's "frustrating." (By contrast, her concerts are always heartfelt and rewarding events.) And when we picked up this book, we thought maybe we'd learn why that is? Maybe Judy would offer some real criticism and insight into her self?

Some might argue that would be expecting too much. They'd insist, "It's an autobiography! People emphasize the moments they want to and they rarely dig in too deep. Even if they wanted to, there's just not time or space."

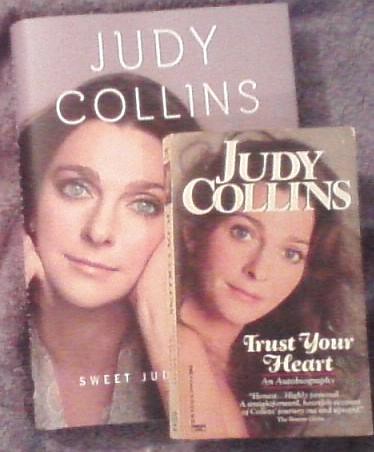

That argument might fly with others, but this isn't Judy Collins first trip to the biography well. Trust Your Heart (1987), Singing Lessons (1998) and Sanity and Grace (2003) precede Sweet Judy Blue Eyes. When you're writing the fourth installment of your biography, it's really not too much to expect that you might examine your work with something other than glancing blows.

Instead, Judy Collins has written another book insisting she is highly desirable. Or was. Probably insisting how desirable she was. We say that because her eyes are still blue yet she chooses a photo from the mid-seventies for her book cover. (The photo on the back cover is from the late 60s.) In between the two photos of the woman in her thirties, the 72-year-old author goes on and on about her past affairs. Yet again. Stephen Stills (who wrote "Suite Judy Blue Eyes" about her) pops up as do many other familiar characters. And as you read (again) of the never ending parade of men, you start to wonder if Judy wants to be seen not as a singer but as a modern day courtesan?

"We got along well and continued to have a great sex life, enlivened by reading The Story of O," she shares of Michael Thomas on page 195, having just shared -- in this chronological biography -- on 191 about "dating Dick Lukins" and "a brief romance" with David Levine. To be clear, our criticism is not about shock or scandal. We're not appalled that Judy's had bed partners (and we know several that didn't make the latest book). We're just amazed that she's written yet another book where everything gets tossed onto the floorboard of the back seat to let whatever guy she's sleeping with ride shotgun.

Women pop up from time to time. Unlike Joan Baez, Judy's not confessing to any same-sex affairs. But women come up frequently in the book as she attempts to settle scores. Mimi Farina has been dead for a decade, her husband Richard for over four decades. "I ADORED Dick Farina," Judy writes. "Mimi later said she thought that was something else going on with us us . . . But she was wrong." (FYI, it's author Judy that puts "ADORED" in all caps.) Other than "bitchy," we're having a hard time figuring out what makes Judy still try to pretend she was closer to Richard than Mimi or to paint Mimi as jealous of her?

Mimi's sister Joan Baez is a bigger target but Judy appears even more immature when writing 'about' that rival. Throughout the book she takes aim at Joan -- while insisting she was always the better person (for example, Joan mocked Judy's lisp but Judy insists that she laughed at Joan's imitation). But the one-sided feud really grates when, for four paragraphs, Judy wants to set the record straight that Bob Dylan wrote "I'll Keep It With Mine" for her and not for Joan, telling readers of arguments and lawyers and Joan insisting that it was written for her and refusing to record it after Judy had already done so. All this for a very insignificant song in which the subject (whether "you" is Joan, Judy or someone else) is never as important to the narrator as his own self-glorification (only he can save the "you").

Carole King is fobbed off twice, the most telling moment when she appears for no reason as "the power of the song-selling machine that throbbed behind Carole King's music and that of other writers in the Brill Building stable." If you didn't catch that "machine" isn't a compliment in the Collins' canon, she's explaining that real artists "including Leonard [Cohen], Joni Mitchell, and others, would try to build a following for their songs by singing them in clubs" but couldn't compete with the "machine."

Ah, yes, Joni. Carly Simon's written of in such a way that you might think she was an actress. In other words, Carly pops up in a sentence here and a sentence there and only in one paragraph where Judy mainly notes Carly's stage fright and that she had once performed in a duo with her sister Lucy as The Simon Sisters. We mentioned Judy was on Elektra. Who was the label's best selling female artist? Carly Simon. And Carly is the only singer-songwriter of her peer group -- male or female -- who can boast of having won a Golden Globe, Academy Award and Grammy for song writing. Don't expect any of that to make it into Judy's book because if Judy couldn't even the score a little by obscuring all of that, what would be the point in writing her fourth autobiography? Other contemporaries (rivals, apparently) such as Janis Ian, Buffy Sainte-Marie, Judy Henske and countless others are reduced to unidentified names in single sentences. But with Joni, Judy's hunting bear.

It's as if the damage Judy did to Joni with her recent cover of Joni's "Cactus Tree" -- featuring Judy's teeth grinding notes on "busy" ("while she was busy being free") -- wasn't enough. No, she wants to dish in that passive-aggressive way that's become a Judy Collins hallmark. And that brings up an interesting point. How the hell did she never deal with her passive-aggressive nature? It's as puzzling as her two decades as an alcoholic in denial while in therapy. (Not mentioned in this book, a lover once accused her of being addicted to therapy.) What were all those sessions for?

Apparently to talk about herself and how wronged she was. More than any other woman, Joni registers in Judy's latest tome. Pages 215 through 219 primarily deal with Joni (who gets many single sentences mentions elsewhere in the book and another minor section later on). Though it's less space than she devotes to longtime rival Joan, it's much more telling.

As Judy remembers it, she brought Joni and singer-songwriter Leonard Cohen together for their "love affair" shortly after she (Judy) woke up "in bed with a man I did not know who was coming down from an acid trip and wanted me to 'comfort him,' no sex was involved. Leonard sat in the room with us, singing 'The Stranger Song' softly to himself . ." What any of that has to do with Joni is only a question if you didn't realize that Judy never landed Leonard and, if she's about to acknowledge his affair with Joni, she first wants us to know, again, what a hot little number she once was.

From her bed scene, she immediately (same paragraph, page 218, if you don't believe us) launches into, "Joni wrote 'That Song About the Midway' about Leonard, or so she says."

"Or so she says" is Judy's first flash of passive-aggressive on Joni, but not her last. In the midst of allegedly telling Joni's story, she leaps several months ahead (without noting that) to describe her nude photo session for the Wildflowers album (none of the photos were ever used) to, again, remind you what a hot little number she once was. As if to say, "Joni might write great songs, but let's put that aside so I can share my nude photo session" (which she describes as "too daring").

"I thought we were friends," she writes on page 216 before launching into trashy dish about Joni giving up a daughter for adoption. (Judy has no knowledge of this topic other than what she's read, FYI.) By page 217, she's insisting, "Joni can be touchy and sometimes distant" and then adding "but all of us have complicated lives." By page 219, she's playing the ultimate victim, "I also wonder whatever happened to the friendship I thought I had with Joni. She disappeared from my life, and in spite of my efforts to reclaim that closeness, there is still a wall I cannot fly or climb over."

This is a ghastly book. It only becomes more horrid near the end when Judy starts including letters from her son Clark (who took his own life) that are supposed to testify to Judy's greatness. Those letters make us squeamish because, if she does value them, they should have been kept private. Instead, her son's very real pain appears to take back seat to her efforts to glorify herself. And, if we're really honest, maybe that's why Clark killed himself?

When Judy got custody of him (that's a whole long story, read any of her books, she always brings it up), she didn't alter her life any. What a young boy seeing his mother drunk off her ass every day must have thought never enters her new book -- maybe not even her mind. Nor does she ever wonder what the constant parade of lovers through the home she shared with her son was supposed to mean. As she tells the story, she supposedly wanted custody of her son all along but the mean judge wouldn't let her have it. When his father no longer wanted to raise him (for whatever reason), Clark was sent to Judy. Judy who took her sister on tour with her overseas, but not her own son. Judy who toured the country non-stop but without her son. And when she was 'home' he's having to compete for attention with the latest man to share her bed?

A seven-year-old boy who's already been separated from his mother for years now gets abandoned by his father, relocates to NYC and his mother doesn't alter her own schedule and desires in the least? Judy Collins was a working woman. We get that. No one's saying she shouldn't have toured or recorded. But was it really necessary to, for example, spend six months on a play (she's no actress, check out her brief role in Junior)? You pay the bills, you use concerts and albums for your art, you can even have lovers. But you have to carve out a space for your young child who has just come to live with you. Fobbing him off on your housekeeper so you can visit your lover across the country filming a movie or calling trips with a lover a "vacation" with your child because you let your child invite along a friend? That's not maturity or responsibility and, as you wind down your 20s, claiming you were a "child too" is laughable.

Though not fully honest, she was more honest in Trust Your Heart. Explaining 1969 and 1970, how she and actor Stacy Keach found a new apartment to live in, how she traveled to Chicago to testify at the Chicago Seven trial (without Clark), how she went to LA (without Clark) to appear on Glen Campbell's TV show, how she went off to Kent State (with Ramsey Clark, Ted Kennedy and Averell Harriman -- but without her son Clark) to speak, how from March through August she was focused on performing in her first play, Joe Papp's Peer Gynt and how she was recording her Whales & Nightingales album, her Hollywood Bowl concert, working with Blood, Sweat & Tears, doing the Dick Cavett show, and on and on until, finally, on page 169, this pops up:

Before Christmas, Clark was caught smoking pot at school. He was eleven by then and had grown up fast living with me. I smiled and looked confused if he drank, and was furious when one of our friends turned him on to pot. As a result of my feelings of frustration, he either did pretty much what he wanted or we fought about what he couldn't do. Whether I let things go on or not depended on my ability to cope at the moment. He was quick to remind me that I was practicing a double standard.

"How come you and Stacy and your friends can do this stuff and I can't?" said Clark, almost looking me in the eye.

When a moment like that happens, a parent -- mother or father -- needs to get real. And the first place you should get real is about your own life and why you allowed your child to see you drunk and your friends drugged all the time? How you ever thought that was appropriate? Before you can even address his problem, you need to make a few adjustments in your own life.

Unless you're too busy being a hot little number. In which case, a kid -- one you claim you wanted -- is a little too much reality for you so you get rid of him.

Yes, when he's caught with pot, Judy sends the son (that she swears in every book she wanted to raise) off to school in West Virginia, far, far away. Genetically, it was never a surprise that Clark would turn into an addict. But to pretend that the environment he was being raised in was no influence is appalling. Equally appalling is that in this fourth book about her own life, "hindsight" has provided no insight to Judy about her son who took his own life.

He did so five-years after her 1987 autobiography Trust Your Heart -- which ended with a paragraph declaring, "The years of struggle for Clark are in the past, the dark times and the hearbreak." Maybe the fact that he was then alive is why Judy felt she could be a little more honest about her son's life?

In her latest book, the incident we quoted above is reduced to, "In January 1971, Clark was packed off to a boys' school in Maryland." Nothing about the pot smoking, nothing about the confrontation. She's too busy including that Faye Dunaway was intimidated by her because, again, she was such a hot little number.

Then Clark's in a sledding accident (a fractured skull and he could die, we're told in Trust Your Heart, but it's just an accident to be passed over in the latest book) and, once he's recovered, Judy packs him off to a school in Vermont. Meanwhile Judy heads to California with her latest battling lover (Stephen Stills has been followed by Stacy Keach at this point as her serious love affair). Clark pops back up when "Clark's addiction" (Judy's a full blown alcoholic by this point, though her latest book skirts this) flares up and she sends him to a new school in Lenox, Massachusetts.

Four pages later, after including compliments and praise for herself, she suddenly notes "my son Clark overdosed at Windsor Mountain School in Massachusetts. We had hoped the staff and the environment might help him stay away from drugs. But once again, we failed to treat his problems effectively, because no therapist understood that his problems were not emotional but the result of a genetic tendency to addiction [. . .]"

We? Clark is a child (16 at the time). Who is the "we"? Judy made the decisions. As for "genetic tendency," yes, that allowed his addiction but what repeatedly triggered his use?

Finally, in 1978, she gets sober: "Clark was nineteen in the middle of a long stretch of drug use when I got sober." She quickly ticks off events -- which really don't appear to indicate she took part in his therapy -- surprising since he went to Hazelden in 1984 and you'd think family sessions would be part of his treatment -- and writes of his suicide, "At times I wanted to kill anyone who may have been in any way responsible for the pain he was in. But I had to let go of blame and anger, for if I held on to it, it would destroy me." Anyone? Really? Anyone? She'll go on to note that she had to make the "choice" not to drink after Clark's suicide so -- at least with regards to her own recovery -- she is aware that she has an addiction and that emotional problems can lead to it becoming full blown again.

If she hadn't included the part about Joni's child, we would have been silent on Clark. Most people have been. Most have walled off the entire subject since his death and treated her rare utterances on the subject as "insight." Joni never spoke to Judy about the daughter she gave up for adoption, Judy never met the daughter. There was no reason at all to include the daughter in the book other than to be passive-aggressive yet again. So if Judy wants to go there, we will as well.

Someone needs to get it through her thick skull (and possibly wet brain) that it was never "we," despite her ego. She wasn't Clark's contemporary, she was his mother. She failed to provide the child with a stable home -- indicating the judge was correct not to grant her custody in the first place -- while traveling through one alcoholic-soaked affair after another and when the child's problems were so extreme, when he cried out in despair by getting caught at 11 smoking pot, she didn't deal with it. She packed him up and sent him off to school out of state so that she could continue her affair. Again, that hot little number. When things got worse and he nearly died -- still age 11 -- she didn't bring him home and show him the love he needed. Instead, she sent him off to another out of state school.

If you're not grasping it -- she so evasive in this book, Clark comes to live with Judy in December 1967 when he's seven-years-old. By January 1971, she's packing the 11-year-old off to an out of state school. After spending years -- though not noted in this book -- claiming that she entered therapy to begin with, in 1963, due to the deep hole losing custody of Clark had created within her. Would it have been Freudian for the self-professed hot little number to have called her latest volume This Hole Filled?

When you write your fourth autobiography, people have a right to expect that this time you'll go deep. When you write about your own son who killed himself, and it's 19 years after his suicide, people have a right to expect you'll explore and not put the blame on others.

Long ago, it should have been broken down for Judy. Her son had abandonment issues from an early age because she left (and then later tried to sue for custody). At the age of seven, already feeling one parent had abandoned him, Clark was pushed away by his father (who gave him to Judy). From ages seven to eleven, she not only didn't alter her previous schedule, she took on additional tasks and left him with her housekeeper. Desperate for attention and wanting to be a part of her life, he did what she and her boyfriends did (drugs). It was a cry for help. Instead of helping him, her response was to begin sending him to a series out of state schools. This was done to a child with abandonment issues. She exiled a child with abandonment issues. (To be very clear, she could have just found him a new school in NYC. She could have handled the pot thing any number of ways including, "You can smoke it in our home around me, but not at school." Though we're sure we'll be accused of being the prudes by someone, she's the one who treated a joint as just 'too much for me to deal with!') All he wanted was to be wanted. Not mentioned in this book, but in others, around the age of 17, Clark leaves one of his out of state schools. He runs away. After he's run away, he calls Judy and tells her he's fine and just needs to be alone so don't look for him. Someone who calls after they've run away to say "don't look for me," is someone who wants to be looked for. Again, his whole life, his sole motivation was to feel wanted. Not getting that as a child created emotions that were most easily silenced through the use of drugs.

Judy has never written one word -- in all four of her autobiographies -- indicating that she understood her son's inner ache or longing. All these years later, she still hasn't done it. But damned if she can't tell you about this man she slept with and what he thought of her and how hot the person he worked with thought she was and Faye Dunaway was intimidated by her and blah, blah, blah.

If you're not getting what Clark had to put up with, you haven't read the book. Janis Joplin pops up very briefly on a page here and there (about five) including 239 where Judy writes, "At the Monterey Pop Festival, where we had first met, I stood backstage ats the lights swirled around Janis. Her voice was big and raw, hanging over the festival like the moon. By the end of the night . . ." And that's it for Monterey. The first real rock festival and that's all Judy has to share. The Mamas and the Papas closed the festival (and Lou Adler and Michelle and John Phillips organized the festival), Jimi Hendrix did a name making set, the Who were on fire, Otis Redding and the Jefferson Airplane were as well. Other performers included Laura Nyro, Steve Miller, Simon & Garfunkel, The Byrds, Buffalo Springfield and The Grateful Dead. Yet that's all Judy has to say?

It reminds us of when she goes to Woodstock on its final day and 'forgets' to tell you about the performances but does note that Bill Graham "invited me to go on stage in the helicopter to watch the festival up close. I thought about all those artists who had been invited to Woodstock -- from Richie Havens to Joan Baez to Crosby, Stills and Nash -- and said thanks but no thanks." And that's Judy 'coverage' of Woodstock in full. This is the woman who can and does go on for paragraphs about her taping an appearance of The Muppet Show but she can't tell you details about Monterey or Woodstock? 'If I couldn't perform,' she seems to say about both of the big rock festivals in the last half of the sixties, 'I'll be damned if I note anyone else.'

And she'll be damned if she takes any responsibility for anything either.

Take her puzzlement over the end of her 'friendship' with Joni Mitchell. Judy was a raging alcoholic and a nasty drunk. She really seems unaware of just how nasty she was or how many people she hurt. And while she works overtime to portray herself as a hot little number, she seems unwilling to admit that other women might want something else. Joni, for example, had to fight, in a male dominated rock world, to not just be taken seriously but to be given her due. She has guarded that accomplishment, tended to it.

And it really doesn't help her art when Judy insults her work by getting her songs wrong (Court & Spark's "Just Like This Train" is not, as Judy's billed it in a previous book "Jealous Loving Will Make You Crazy") or by crediting David Crosby as producer of Joni's first two albums. Or by refusing to record Joni's songs. It wasn't Bob Dylan that wrote Judy's only top ten hit, it wasn't John Lennon and Paul McCartney and it wasn't Leonard Cohen. Yet Judy's recorded three full albums exploring those songwriters while ignoring Joni. She knows the message that sends.

She was a lousy 'friend' in real time and she's done nothing to help Joni as an artist. In fact, she's done everything she can to tear Joni down. If you doubt us, here's a typical Judy interview -- Larry King, June 23, 2001:

KING: What's your first hit?

COLLINS: My first hit, real hit, was "Both Sides Now" in '68. In '67, I recorded Leonard Cohen's music and I discovered a lot of singers whose songs I love and this was before I started writing my own songs. So, I was very fortunate. But I didn't have an immediate -- yeah, I worked very hard. You know, I was always singing...

KING: You were known.

COLLINS: And I was very well-known, but I didn't -- people did not start to answer my phone calls until about 1968.

KING: "Both Sides Now" was enormous though, right?

COLLINS: Enormous hit.

KING: Great song.

COLLINS: Enormous hit. It was...

KING: That was a breakthrough song, right? It was folk and beyond, right?

COLLINS: It was a breakthrough, yes. It was folk and beyond and I think that was really the thing that set up the idea that I have about music and my own writing, which folk music, people call this folk music, I'm not sure what it is. I think it's alright to call it that. But, there's music about issues and about feelings and poetry and politics.

KING: Has your voice changed as you get older?

Who wrote Judy's "first hit" (and biggest)? To have caught that discussion, it must have been Leonard Cohen because he's the only name she mentions. But again, it was Joni. And it's that sort of refusal to treat Joni with respect that's going to guarantee that they're not friends. Equally true, Judy wants to 'forget' (she remembers) many events, like inviting Joni to a worshop and then 'forgetting' to take her. Judy was so big with the promises and so bad at keeping them. She can blame it on her disease, if she wants, but her treatment for that addiction was supposed to include an inventory and accountability. Judy writes as if twelve steps can be ignored and all that's necessary is to repeat war stories with cash register honesty over and over.

And be bitchy. Mavis Staples pops up so Judy can chuckle over Mavis' belief that Bob Dylan sincerely proposed to Mavis. Bob Dylan is a straight man. Mavis is a woman. Bob is known for his relationships with African-American women. Mavis is African-American. Bob has always been keenly interested in gospel music and Mavis got her start in gospel and her family group, the Staple Singers, was one of the biggest gospel groups in America. Why is difficult for Judy to believe that Bob Dylan could have been serious when he proposed to Mavis Staples? If you click here and listen to this December 20, 2008 Wait, Wait Don't Tell Me! (NPR) audio segment, you'll hear Mavis explaining that Bob asked her father if he could marry her -- a fact that Judy's ignorant of.

She's not ignorant of changing moods in the public's taste. Unlike in her previous three autobiographies, this one finds Judy suddenly 'tight' with Phil Ochs. While so many of the other stories are retold (such as dropping acid with Michelle Phillips), the Phil Ochs material is new and 'novel.' So is the claim of her great friendship with Lillian Roxon. What the 'novel' new material really indicates is that Judy's paid attention to the festival circuit -- at least enough to be aware of the recent documentaries on both Ochs and Roxon and that including the two of them might make her appear more relevant in this book.

This book. "Hard Time For Lovers" was 1979. It's 2011 and it's hard times for the economy. $26.00 is the list price for Judy's 'new' book. Except for nine pages, the very same time frame this book covers was covered in 1987's Trust Your Heart which is better written and more honest. Best of all, if you find Trust Your Heart at a used book store, you can probably get it for at least half the $4.99 (paperback) cover price. In a tough economy, it's not just the bargain, it's also the only volume worth reading.