100th anniversary of Bread & Roses strike

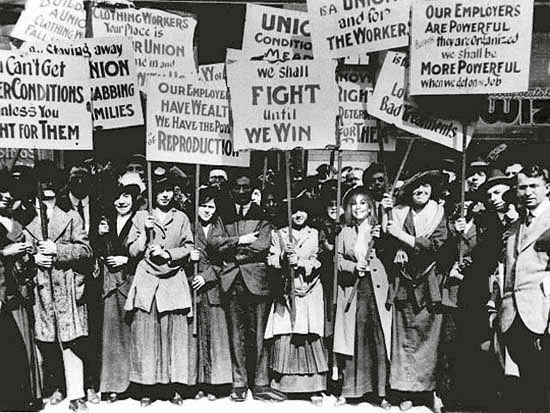

Women textile workers on strike in 1912, Lawrence, Mass. |

On this International Working Women’s Day, March 8, it’s instructive to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the Bread & Roses strike, which provides valuable lessons for our struggles today.

The March 12 date marks the end of the two-month strike of 25,000 textile workers in Lawrence, Mass., which was the center of the New England textile industry. It’s estimated that one company annually produced woolen and cotton goods worth $45 million — an amazing sum 100 years ago!

But the companies did not share that wealth with the workers, who averaged less than $9 a week. Living and working conditions were so bad that a Lawrence physician reported that “thirty-six out of every 100 of all men and women who work in the mill die before or by the time they are twenty-five years of age” due to malnutrition, occupational diseases and speed-up.

Known as the Bread & Roses strike — because at least half the strikers were young women between 14 and 18 who carried signs reading “We want bread and roses too” – this work stoppage offers a shining example of how the unity, organization and determined spirit of the workers stopped corporate greed and the police state that imprisoned strikers on its behalf. It also shows how a strike can become an incipient revolution.

Strikers organize, invent new tactics

What provoked the strike? The state of Massachusetts, responding to notoriously harsh working conditions, passed a law effective Jan. 1, 1912, reducing weekly hours for women and children from 56 to 54. On Jan. 11, when Polish women weavers noticed their weekly pay had been cut by 32 cents (which would deprive them of three loaves of bread), they shut their looms and marched to all the other factories, shouting “Short pay, short pay!”

The next day, all the mills were silent, as the workers from 30 countries, speaking 45 languages, held a mass meeting. The socialist-oriented Industrial Workers of the World, organizing in the mills since 1907, telegraphed experienced IWW organizer Joseph Ettor to help organize the strike.

Immediately, Ettor set up a strike committee, with two representatives from each nationality, which met every morning to plan the day’s activities. Mass picketing was conducted daily. The strikers issued demands: a 15 percent increase in wages, double time for overtime and no reprisals for striking. Ray Standard Barker, writing in the American Magazine, called it the first openly socialist strike because its demand for higher wages was tied to the abolition of the entire wage system and of private ownership of industry.

Answering the call for organizers, Arturo Giovannitti, editor of the Italian Socialist Federation’s newspaper, set up strike relief, with a network of soup kitchens and food distribution centers run by each national group. Volunteer doctors provided medical care. In response to a national appeal, donations poured in and were distributed equitably, so no one was evicted from company housing.

The picketers invented a new tactic — an endless chain of thousands marching around the mill district wearing white armbands reading “Don’t be a scab.” (There were none.) Large groups also locked arms on business district sidewalks, and when local cops and militia tried to disperse them, the crowds went into stores, clogging the aisles.

But picketers were not allowed to protest peacefully. Police violence and arrests began the first week. When strikers, who after being drenched with water from fire hoses, retaliated by throwing chunks of ice, 36 were arrested and sentenced to a year in jail.

One of the largest demonstrations occurred on Jan. 29, after Ettor addressed a mass meeting on the town commons. When militia, summoned from neighboring towns, tried to halt the march, Ettor averted violence, leading protesters down a side street. Later that evening, a woman striker was killed when police tried to break up a picket line.

Even though Ettor and Giovannitti were at a meeting three miles away, they were arrested as “accessories to the murder,” charged with inciting violence, refused bail and imprisoned without trial for eight months. In April, striker Joseph Caruso was charged with the murder, though protesters identified a Lawrence cop as the killer. Martial law was declared, public meetings were declared illegal, and 22 more militia units were called in.

Not deterred by police state tactics

Police state tactics did not stop the strikers. IWW organizers Big Bill Haywood and Elizabeth Gurley Flynn joined them. After Haywood addressed thousands of strikers on the commons, they serenaded him with “The Internationale” sung in their native tongues. “Those kids should be in school instead of slaving in the mills,” Haywood responded.

Adopting a strategy employed by French and Italian strikers, the workers, assisted by Mother Jones, sent 120 children to New York City on Feb. 10, where they were welcomed by 5,000 Italian socialists, who fed, clothed and housed them. After another group of 92 children were sent there a few weeks later, Lawrence officials, outraged by the sympathetic publicity generated, ordered that no more children could leave the city.

On Feb. 24, as 150 children were to leave for Philadelphia, police and militia waded into the crowd, swinging billy clubs as they tore children away from parents. They arrested 35 women and children, beating them mercilessly on their way to jail. That display of heartless brutality was the turning point in the strike.

A national outcry ensued, leading to a congressional investigation in Lawrence in early March. When truth about the horrific working and living conditions emerged, the biggest textile company capitulated on March 12, accepting all the strikers’ demands. Soon, wages were raised for all textile workers throughout New England. It took a two-month trial in the fall before Ettor, Giovannitti and Caruso were acquitted on Nov. 26.

Unfortunately, however, no contract was signed and the union floundered. During the 1913 recession, workers’ wages were once again cut, and speedup became even more ruthless.

But the heroic example of the Bread & Roses strike endures. The key elements were unity of the workers, though divided by language and nationality; inventive tactics that exposed the wrongs and demanded rights; and openly promoting the strike as a struggle against capitalism and for socialism.

It’s time to adopt similar strategies inspired by this struggle to counter the current war against the working class.

Sources: Joyce Kornbluh, “Rebel Voices: An IWW Anthology” (Chicago: Kerr, 1988); and Milton Meltzer, “Bread and Roses: The Struggle of American Labor 1865-1915” (New York: Knopf, 1967).

Workers World, 55 W. 17 St., NY, NY 10011

Email: ww@workers.org

Subscribe wwnews-subscribe@workersworld.net

Support independent news DONATE