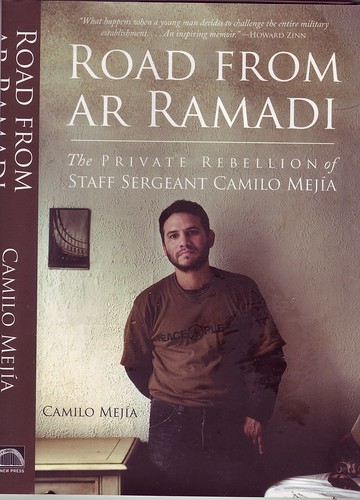

Jim: This week we have a book discussion. Participating are The Third Estate Sunday Review's Dona, Jess, Ty, Ava and, me, Jim, Rebecca of Sex and Politics and Screeds and Attitude, Betty of Thomas Friedman Is a Great Man, C.I. of The Common Ills and The Third Estate Sunday Review, Kat of Kat's Korner (of The Common Ills), Cedric of Cedric's Big Mix, Mike of Mikey Likes It!, Elaine of Like Maria Said Paz, and Wally of The Daily Jot. The book in question is Camilo Mejia's Road from Ar Ramaid: The Private Rebellion of Staff Sergeant Mejia. Mike, set us up.

Mike: Camilo Mejia's Road from Ar Ramaid: The Private Rebellion of Staff Sergeant Mejia was published by The New Press and on sale the first Tuesday of this month. The list price is $24.95. It's 300 pages of text, contains an editor's note and an afterword by Chris Hedges. Camilo Mejia is a war resister and the first war resister who served in Iraq, or the first public one. He tells his story prior to enlisting very quickly and the bulk of the book focuses on his time in Iraq.

Rebecca: That was actually my only problem with the book. The book basically ends in May of 2004. To me, what has gone on since would have been just as interesting.

Kat: Like his time in prison for refusing to serve in the illegal war?

Dona: Backing up, Camilo Mejia self-checked out while on leave in the United States, went underground and turned himself in. After turning himself in, he was court-martialed and sentenced to a year behind bars but served a little over eight months.

Rebecca: Right. The book ends, his narrative ends with the verdict. The editor's note comes after and reminded me of the ending of American Graffiti. Three years is a lot of time and I would have preferred to have heard about that from Mejia.

Ty: Maybe there will be a sequel to the book.

Rebecca: Anyone who saw More American Graffiti won't rush for a sequel.

Wally: I understand what Rebecca's saying. I even agree with her. The book's got a lot to offer and you'll be flipping the pages quickly but with that editor's note about what Camilo did while serving his time and about how he went back to college and is scheduled to graduate this month, those are things that should have been shaped out by him. I really liked the book. If the editor's note hadn't been included, I probably wouldn't have felt, "Where was that stuff?" But when you read the editor's note it really does point out that the story wasn't finished.

Cedric: The big surprise for me in the book was his story because I thought I knew it. He's usually considered the first public war resister. There's another guy --

C.I.: Stephen Funk.

Cedric: Right, Stephen Funk. He comes before and he refused to deploy to Iraq. So Camilo Mejia is the first to refuse to re-deploy or the first to have served there and become a war resister as a result. But the legal issues were all new to me and I really had thought I knew the story.

Jim: You're talking about status?

Cedric: Right. He's serving in the US military and he's not a US citizen. He's not the only one and I'm aware that happens; however, with Camilo, because of his status, the military was legally compelled to release him before he ever self-checked out. I don't know how to word it any better than that.

C.I.: I think you explained it fine but, if anyone's confused, a non-citizen cannot be extended in the US military after eight years.

Cedric: Thank you, that's it. The eight year thing. So Camilo's eight years expires when he is in Iraq. Again, I had followed, or thought I had followed, his story in the limited press it received but that was a new detail to me. Camilo was a resident, enlisted as such, had met his obligation and legally the military was required to discharge him because he had come to the eight-year mark. I'm not saying he shouldn't have self-checked out, I am saying that he shouldn't have had to because the military should have lived up to their own guidelines. I remember the Dan Rather interview airing --

Ava: 60 Minutes II.

Cedric: Right and I don't remember that being in there. Maybe I've forgotten it. But his mother had a senator --

C.I.: Ben Nelson.

Cedric: Ben Nelson working on this. This was all going on before he self-checked out and I have no idea why this wasn't an issue in the court-martial but, as I read the book, it was never brought up. That was probably what stood out most to me in the book. I enjoyed it and his stories from Iraq are more than worth reading but what stood out to me when I was reading it and what still stands out is that the military was required to discharge him and they didn't. Only after that did he self-check out.

Elaine: I think that's a strong point and, if it was stressed, I missed that coverage in real time. I think that's a theme in the book actually: the military not meeting obligations. I think that's true when Mejia and those serving under him are under fire and they follow the standard procedure, by the book, which is to keep moving. Once they're back on base, Mejia and another man are getting chewed out by superiors for following procedure. And for letting the 'enemy' know that they were 'afraid.'

Betty: I marked that as some thing to highlight. I'll note this, from the end of it, on page 76:

Gallegos, Rosado, and I looked at one another, not saying a word. Just minutes before, we had celebrated the fact that we made it through an ambush untouched. Now we were dealing with a command that was asking us to expose ourselves unnecessarily to serious danger in order to "send the right message." They knew damn well that we had acted according to regulations, just as we knew that it was our asses on the line while they were safe back at the base. I left the command post with my two team leaders, wondering who the real enemy was in Iraq, and just how close we were sleeping from it.

Betty (Con't): In the stories you hear, and certainly in relation to the attack two Saturdays ago where it appears the 4 US soldiers and 1 Iraqi translator who died as well as the 3 US soldiers who were kidnapped, had been sitting ducks, this really does stand out. Or it did for me. And, obviously, Elaine as well.

Elaine: Because you have to wonder whether that was some petty throw-the-weight-around nonsense or is about something greater?

Ty: Because this is a detail that repeats. You'll hear it or read it in various accounts. I'm not suggesting that those ranking higher, in these stories, are wishing that the soldiers would die, but I am thinking that they're willing to take greater risks than are necessary because they're looking for decorations.

Mike: Decorations for the actions of others. And, like Camilio says in the quote Betty read, their asses are safe back at the base.

Jess: Along with those similar stories, there was also, to me, a sense that some of the missions, especially the ones where they're being sent out when they've just returned and are supposed to be getting sleep, there was a sense that these missions weren't important in any strategical manner. I don't think it was someone being petty and throwing the weight around, I do think, and I'm remembering Joshua Key's stories about late night home raids in his book The Deserter's Tale, it was done in an attempt to piss the ones going out off, to keep them pissed off and angry. I think some of the aggression and abuse stems from that. And I do think creating the anger, if not desiring the abuse as well, is planned from above.

Jim: That's the book Key wrote with Lawrence Hill, The Deserter's Tale. And just FYI, we discussed it and Peter Laufer's Mission Rejected: U.S. Soldiers Who Say No to Iraq, in "2 Books, 10 Minutes" back in March. Any thoughts on what Jess just said?

Elaine: Well, I mean, isn't that what boot camp is all about? Isn't that what they do, with the stabbing the dummy and screaming racial slurs?

Dona: Oh, careful, Elaine. Didn't you know that's suspect?

Elaine: Sorry, I don't know what you're talking about.

Dona: I'll be kind and not name the reviewer but he was shocked, SHOCKED, by Key's account of boot camp and had to add that he really couldn't see that happening.

Elaine: You're kidding.

Dona: No, I'll e-mail you that review.

Elaine: Well you know, and Dona does know, that story's not exclusive to Key. Vets have told Matthew Rothschild similar stories on Progressive Radio. It's in Laufer's book, it's even been in some mainstream news reporting. I'll assume the reviewer has had his head in the sand, or elsewhere, and somehow managed to repeatedly miss that for the four plus years that the illegal war has dragged on.

Ava: That's the reason Camilo Mejia needs to share his story and others as well. C.I. and I were talking about that specifically because, like Dona, we know that review. And until you've got a large number explaining that it did happen, that it does happen, you will always have reviewers like that who will make ridiculous claims.

C.I.: And this is another valuable resource for today and for tomorrow. I know Rebecca's not trashing the book. She's offering a valid opinion and from the way Kat spoke, I think Kat strongly agreed with her. So maybe we should return to that?

Jim: Is that right, Kat?

Kat: Yeah. That is a huge part of the story and I don't think it got the space. It didn't get the space. That's not a "think," that's reality. If you meet someone who has self-check out and he or she talks about their plans, they do float the idea of turning themselves in, we all know that, we've all spoken to some. And what's the first question they ask? About imprisonment. Not, "Oh, could I make it in jail?" They're concerned about how they will be seen by others who are confined. I'm not suggesting anyone should turn themselves in, I am saying that's the thing that anyone who has self-checked out is going to be flipping through the book for before they start reading.

Rebecca: And they will be disappointed because, while the editor's note can tell you that he had conversations while imprisoned and that he read books then as well, there's nothing from Camilo about it. I'd also add, and I'm going to assume everyone here knows which one I'm referring to, but there is someone who has self-checked out and is most interested in the reactions that other people have to you. That's not a part of this book. We do get to hear about two soldiers that show up to testify at the court-martial. I'm not saying, "Don't read the book!" It's a strong book worth reading. I am saying that it doesn't provide what people currently in Camilo's situation are necessarily looking for.

Jess: And maybe when Kevin and Monica Benderman's book is published, we'll get more on that.

Elaine: I would guess we would.

Dona: As I'm following along in my head, it appears to me that Mike, Betty, Ava and C.I. have said the least and Ava and C.I. have used a lot of time to clarify something. So I think it would be good to turn it over to them.

Jim: As we wrap up? Yes. Okay, Mike why don't you grab first.

Mike: I think we've given some really strong examples of the book. I'm not sure whether to toss out something new or just back up a point. So I'll do sort of both. While he's in Iraq and while he's underground, he misses his daughter Samantha. So why do we get this in the editor's note. I know we're hurrying, I'm looking it up quickly.

C.I.: Page 302.

Mike: Yes, thank you. "According to Mejia, the worst moment he experienced in his almost nine months in jail was the one time his daughter, Samantha, came to visit him. Seeing her and then watching her leave without him at the end of the visit made him feel like a real prisoner, like something essential in his life had been taken away." That's an editor's note?

Betty: Yeah. I hadn't thought about the point Rebecca raised early on in the discussion until she raised it. It flew over my head and I didn't notice it -- a sign of how involving the book is -- but I agree with Mike, that's not an editor's note, that's something the author needs to tell. It's too important to be put in an editor's note. That needs to be in the text, not in a note. That's not to insult the book that is written. It's a great book and we all enjoyed it. But that point, better than anything else, underscores Rebecca's point. Now, personally, I would have enjoyed a bit more on the underground days but I'm assuming we can only know so much about those because the network still exists and Camilo's being tight lipped there so that others may benefit. But while I can think about that and understand why more isn't shared, something like "one of the worst days" really is something that we should be hearing about from Camilo himself, not from an editor's note.

Ava: I agree completely with Betty, Rebecca, Mike and Kat on this point. But at 300 pages, I'm not sure what you do? Do you go on for fifty more pages? A hundred? I would have been all for it. It was a page turner. I could have kept reading for many more pages. But I think 300 was considered the maximum limit and I'm wondering what would have been cut out to provide the space for what's missing?

C.I.: Which is a good point. And though Ava stopped, I think actually she wants to add something.

Ava: I do. Um. I think it's obvious that this was most likely an editorial decision. And I think it was the wrong one.

C.I.: The way it ends, Camilo has been sentenced and is being taken away and someone may have seen that as cinematic but that's not the end of the story. Mejia has taken part in speaking out and in rallies and demonstrations, not to mention the march that he and other Latinos devised in March of last year: Peregrinacion por la Paz, the March for Peace. Those are important elements of the story and they should have been included. To give the editor the benefit of the doubt, if Camilo Mejia wasn't able to write about such things, the answer is for a Q&A chapter where these and other topics are addressed quickly, briefly and in the author's own words. Lastly, Also on Monday, you can hear Camilo Mejia in his own words, and war resisters Pablo Paredes, Michael Wong and Jeff Paterson on WeThePeopleRadioNetwork.com's Questioning War-Organizing Resistance this Monday from 7:00 pm to 9:00 pm PST.

Jim: So to sum up, everyone recommends the book. You will find it hard to put down. Like many good books which hold your attention, you will be disappointed when it ends and you may also feel that it ends without dealing with some of the issues that begin with imprisonment.